CULTURAL PROFILE OF DR. FOUZIA SAEED

Area of specialization: Women in Folklore

Dr Fouzia Saeed, with a PhD in Education from University of Minnesota, USA, has been working on women’s issues in the field of folklore, development and social change. Her career started as a Deputy Director Research at the Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage (Lok Virsa), where she developed and supervised a folklore research program and contributed to improvement of the folklore archives and the library of the Institute. She herself has done research on various aspects of folklore, through the Institute and on her own. The book, Women in Folk theatre, is the most well known of her work at Lok Virsa. This captures descriptions of the tradition of folk theatre through women’s eyes and their experiences. She has done research on other entertainment forms like folk circus, folk dances and folk natak (drama), and has mostly focused on women’s experiences in each of them.

Her book, Taboo, , is an ethnography that captures the fading traditional systems of prostitution in South Asia, with their close relationships with classical music and dance, as they are steadily replaced by the more exploitative modern brothel systems. The book was published in English and Urdu by Oxford Press has been translated into Hindi and Marathi by nonprofit groups in India. A Japanese translation will be out soon.

Her research on traditional woodcraft and furniture of D. I khan, one of the traditional furniture producing centers exemplifies her work on Pakistani material culture. She also helped put together modest folklore museums in organizations she has worked in, including the Allama Iqbal Open University and maintains her own collection of folk dresses and jewelry.

Dr Saeed has been actively involved in reviving Pakistani folk performance arts through organizations she has been associated with, and is also a folk dancer herself. Through the Folklore Society of Pakistan (www.folklore.com.pk) she, with her peers, re-established the trend of Marwari singing, which had almost died in Pakistan. The revival efforts of this tradition included organizing annual festivals, producing music albums and working with these hereditary musician communities to empower them. She has also worked on traditional culture and social change through Action Aid and the Interactive Resource Center.

She created a youth leadership training camp at Mehergarh: A Center for Learning, where she uses empowering aspects of traditional culture as a main theme. Mehergarh uses culture as a firm base to launch social transformation initiatives. She believes that the firmer we are rooted in our own cultural values the farther we can advance. However, she recognizes that Pakistan has progressive traditions that we need to hang on to and damaging and discriminatory traditions that we should prune in order to move ahead.

She has taught courses on Women in Folklore in the Department of Pakistan Studies, Quaid-e-Azam University as a visiting Professor.

A paper on Women in Folklore

SOUTH ASIAN FOLKLORE : A COMMON LEGACY : Exploring the Roots. Retrieving the Traditions, (September 2007)

Read at the First SAARC conference on Folklore in Dehli, 2007

‘Place of Women in Folklore : in the countries of SAARC Region’

Women in folklore is an area of study that has been well documented. In the developing countries however this sub-field has been more commonly studied from a descriptive point of view rather than an analytical point of view. My paper here is a humble attempt to do a general analysis of women’s position in the folklore of SAARC region with a simple framework. My information draws on my personal observation and experience of research over the last two decades, interviews with women from most of the SAARC countries for this paper and a quick review of the materials available. Though most of my own research is on women in folklore, it has focused on women in theatre and other entertainment roles, women and shrines and women and crafts, this paper looks at the overall positioning of women in the folklore. My framework looks at three significant aspects:

The first one is the commonly held notion that women are the keepers of the tradition. In the folklore of the SAARC region women commonly are held responsible for family related religious rituals, rites of passage especially birth and marriage and other rituals related to celebrations, maintaining family relationships and social linkages. They are not only considered the hub for ensuring that tradition and rituals are followed but also are designated with the role of passing them on to the next generation.

The second element of the framework is to look at the folklore around women and analyze how it facilitates women’s emancipation in the society. Folklore over the centuries has developed spaces for women, which can prove to be helpful and supportive for them. May these be in the form of rituals, folk practices or customs. In addition folklore also provides role models or icons that gives women space of acceptance for deviation or simply examples of empowered acts.

The third aspect will analyze the folklore, which hampers women’s emancipation and becomes an impediment to their rights as a human being. Here I will also look at the role, at times folklore plays to reinforce the status quo from the point of view of the elite in a society and becomes a tool of oppression itself.

I will use examples from different SAARC countries to look at these aspects and will draw conclusions at the end.

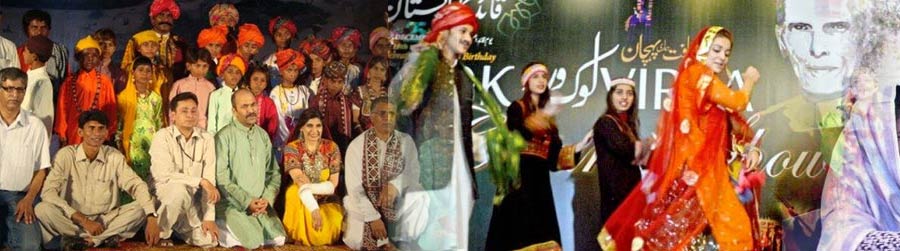

Manganhaar music revival

The fourth Manganhaar Music festival organizaed by the Folklore Society of Pakistan in Karachi. Every year there is a festival and a competition of young students of various baithaks who are learning this heritage from their elders and ustads. Dr. Fouzia Saeed is one of the founders of this Society and is very committed to bring about a revival of this form of folk music.

She with Yasser Nomann, who is the director of the Society put together this festival every year in thier effort to restore the dignity and social status of these musician communities who carry this precious heritage with them. Two clips from the Festival are here for viewing. Full videos of all the festivals are available from Radio City, Islamabad, Lahore or Karachi.www.folklore.org.pk.

Women as keepers of Tradition

Who we have to visit because their mother in law died last month or who do we have to pay a visit because their son passed their civil service exams, or buying of gifts for our cousin’s wedding; all this is usually reminded by wives to their husbands. They keep a tab on who is born and who died in the family. They are usually responsible for making sure that the religious rituals like puja at certain occasions, khatm-e- quran or milad is organized to thank god. They ensure that all rituals and customs are followed in every step of the wedding.

In cultures of South Asia women are the ones who keep the tradition alive by continuing to wear traditional clothes. Men in all the SAARC countries are quick to switch their clothing and mannerism to western styles but social pressure does not allow women to do the same. She is the keeper of the tradition. The society gives her the role to pass on the tradition to the next generation through her children.

In Afghanistan women are not just seen as keepers and embodiment of the tradition but also embodiment of the honour. Which in turn is reflected in many customs, reinforced by traditional phrases, songs and stories. Men can leave their turbans behind, their heavy chappals can be replaced but it doesn’t shake the honour of the family or tribe. Women however have the burden of the upkeep of the tradition, where if they leave their homes, go out and work for money, seen in public (mostly in rural areas) or bring any change in their traditional clothing are not tolerated. Not only do they violate their role as the tradition keepers and therefore seriously threaten the whole traditional culture but the fact that it is intertwined with honour gives the society a legitimate reason to reprimand them. I will discuss these forms of reprimand, which are part of the folklore and are socially widely accepted, in the next section.

Being a good woman is also an interlinked phenomenon of tradition keepers. It is the women who are given the moral burden of being good by showing compliance to the customs and tradition. Thus if Afghan women are good they have to keep themselves form the public eye because that is what good women do. Any one who is seen in public and especially talking to a being of the opposite gender risks being bad and thus in violation of her role of tradition keeper. These norms are not as strict when we talk about urban areas, in this case Kabul but the spirit of it is very similar.

Mothers specifically are given the role of raising brave sons and obedient daughters. If that is not so the mothers are blamed for it. Fathers barely get the blame of children who do not comply to the tradition.

In Pakistan when a man wears blue jeans he is considered “cool”, educated and urban based but when a woman is seen in blue jeans she is usually considered western/modern, too out going, and mostly immoral. Partially it is the social pressure on women not to deviate from the tradition and partially it is the fear of the society that women might make an attempt to change the status quo. In both cases women are considered to be the hub for folklore, tradition and custom.

Aspects of Folklore that Facilitate Women’s Emancipation

Upon analysis of women in folklore in South Asian cultures it is observed that there are several elements of our folklore that are helpful to women in terms of finding their strength.

In Pakistan, mostly in area of Punjab water wells are an important part of the folklore. Women get together to fetch water as a routine activity. This for them becomes, at times, a highlight of their day; A genuine excuse for going out of the house and an opportunity to see and share stories with their friends. There are many songs and folktales that have developed around the water wells. In Nepal also water wells provide a place for women to share their happiness and sorrows.

In Afghanistan women have spaces that they utilize for themselves in a positive manner. Here also the most common are gatherings around the wells. Since water collection is typically women’s role in many parts of Afghanistan’s rural society, women use that platform for networking and getting support from each other. Similarly springs are also used for the same purpose.

Wedding parties are another significant part of the traditional culture where folklore plays its role. People’s lives may deviate from the traditional culture gradually but rites of passage are where they come back to the traditional ways of doing things. Because many activities that are in routine can be seen as inappropriate are considered quite appropriate at the wedding ceremonies, and women make use of it. This includes dressing up, singing, dancing and especially intimate mix gatherings of relatives. Women are fully allowed to dress up, sing , dance and in many case mix with men of their family. In Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal this pattern is quite vivid. Many segments of the society are trying to influence it with the currently dominant norms of “religiosity” but for most part of the countries it remains a space where women do come out and participate in full and enjoy music and dancing which they normally don’t.

In Afghanistan festivals like Eid-e-Nauruz remains an important part for women where they get together with other families and spend time. They do collective cooking which gives them time to interact and support each other. Samanak is a dish that is cooked over night and women interviewed stated that they like being together with other women and sharing their happiness and sorrows all night. It is also a time when women go to the shrines and to graveyards to pay respects to their loved ones. In reality it is time that they have for themselves. Sabzi Laghat (literal translation touching the grass) is a part of this celebration where families go out of picnic to beautiful gardens.

Getting the social acceptance of possession by spirits or gin, has also served women well. The folklore around women being possessed gives the opportunity for women to let go of facades of appropriate behaviors and express their social problems and despair in a socially acceptable manner. This is not just true in Afghanistan but Pakistan, India and Bangladesh also. It is a common practice in some rural areas of almost all the SAARC countries. Though there are problems associated with how these women get their treatment, at least it gives them some path for expressing their anger and despair.

Getting into trance at the shrines is also similar in nature, which is accepted way for both men and women to deal with their despair. For women it serves more as they hardly have space to let go of their acts and dance or go “crazy” in public to follow their feeling and hearts.

Visiting of shrines for praying and making their wishes is considered a spiritual experience where women get to leave home, travel with family or other women and be with women at the shirne itself. They are able to articulate their desires and wishes. At various annual festivals of these shrines, the urs many have one day specifically dedicated to women which gives them the freedom to enjoy themselves without the fear for harassment. This exists all over the South Asia with some shrines more popular for women than others.

In Punjab, which is now in India and Pakistan both, there was a custom called trinjan where young girls were allowed to bring their spinning wheels together and would spin all day in one place. This gave them a place to connect, share and build solidarity.

In Afghanistan older women are allowed to be generous and serve the travelers with food and hospitality. This is not seen as being bad or immoral but according to the folklore is accepted, supported and appreciated. This also provides older women an opportunity to do service for their larger society and also be appreciated publicly.

About 50 years ago there was a pukhtoon tradition in the area of Zhob and surrounding area which allowed young men and women to dance together. It was called Kamar Yami and a similar tradition in Nangahar of Afghanistan was called Brug Attan. It means mixed colours. After that a young man could go to a young woman’s house and could seek permission to meet her. He would call her out for poetry, tappa or Lundi and the parents encouraged the girls to go. They would meet in public and the tradition was called naarey. This took a form of courting.

Just the act of dancing and singing together for women has been and continues to be an empowering act, where they are allowed to get in touch with their creative and aesthetic expression.

In Bhutan the elements of matriarchal system provide an array of folklore that supports women’s emancipation. The tradition of passing on property to women in the Eastern side of Bhutan helps women get the stability and a certain status in the family. Women there are considered to be more important and that reflects in the folklore also.

There have been women heroes in the folklore or icons who have excelled, broken the rules and got admiration. These women were either real and took a special role in our folklore or were imaginary. In Punjab, both in Pakistan and India, Heer from the folk epic of Heer Ranjha provides a strong role model for women. She was courageous, openly expressed her self and fought for what she wanted. Zarghuna Ana mother of Ahmad Shah and Malalai of Maiwand in Afghanistan have legendary place in their folklore. Whese women are the icons for wise vision, bravery and courage.

Folklore As An Impediment To Women’s Emancipation

It is an interesting notion that at times folklore that is romanticize, impinges on the rights of vulnerable segments of the society and is totally used by the elite to reinforce the power status que. This includes folk poetry which strengthens social hierarchy. Showing that there are lower zaats ethnic groups, and higher ethnicities by birth; Songs, phrases, that put them down whenever the elite feel that they are stepping out of line and customs that “put them in their place”.

Similarly for women there are phrases that are considered folk wisdom, but are efforts to “putting them in their place” or ensuring that if they deviated the path defined by the tradition and custom they will be humiliated, put down or reprimanded.

- Egs from other countries

- In Pakistan and northern India

- aurat paon ki juti he a woman is the shoe you wear in your feet

- aurat ki aqal tukhnon men he a woman’s brains are in her ankles

- In Afghanistan and Pakistan’s sarhad province they say

- Da khuzu ze p kor ke de ya gor ke de” A woman’s place is either her home or her grave. This is to ensure she is not seen in public space.

- In Nepal it is common to say

- Swasni manchi alkako sumpati

- A woman belongs to another household. There are two aspects in this phrase. One that a woman has no identity of her own and it fully supports the patriarchy and the second that the word for a woman actually means wife person, which describes a woman only in a relationship.

Using women as a swear word is also found in our folklore where phrases put down men comparing them to a woman. He talks like a woman, he is a coward like a woman, he talks too much like a woman, he is indecisive like a woman, etc.

In Pakistan and India it is said “Kia aurton ki tarah churian pehen li hen ( why are you wearing bangles like a woman, meaning why have you become as coward as a woman)”

In a similar context in Nepal they say ‘chura lagau mard hai na’.

There are other traditions that either are to keep women in their socially sanctioned secondary position or these traditions are abused to accomplish that purpose. A tradition in Bhutan which was initially for both men and women to court, gradually turned not so favourable for women.

A Bhutanese tradition, which is night out for boys and girls. This is a socially sanctioned night out for the young men, where they can go and court any woman they like. The families of the young women accept it and if the couple is very sure about a long term commitment in the form of marriage, the young man stays until the morning. When seen in the morning the family approves their marriage. If he is not interested or the woman doesn’t want him he leaves while it is still dark. The tradition initially was seen as an opportunity for both, where virginity was not a high premium and sexual morality didn’t have a heavy stigma. But gradually this tradition has hampered women more than helping them. It has resulted in pregnancies that women are left with and has inclination of abuse by the men.

In Nepal a young girl is chosen as a deity and is pampered in everyway and is treated like royalty. She embodies a living goddess and is worshiped by all. Once she reaches puberty she looses all that status and is asked to leave the temple. From there on she lives a life of a woman who has a very low status in the society and no one even marries her.

In Pakistan the tradition of honour killing takes the shape of karo kari or siah kari (black deed) where any man and woman suspected of adultery are killed with the sanction of the custom which gives the power to the elite to take life to save “honour”. This tradition while more institutionalized in Baluchistan and Sarhad tribal areas, is also equally pervasive in south Punjab and interior Sindh. The local panchayat or jirga, the local elites in any rural area take a decision on the basis of tradition. Marityudand and other forms of honour killing in India, Bangladesh and Afghanistan are very similar in dynamics. Though the custom is to punish both men and women, it is usually women who are sacrificed. Mostly this custom is abused where a brother kills a man because of a family feud, comes home and shoots his sister to make it look like an honour killing, thus getting the sympathies socially and legally. The custom sanctions death of women and inculcates a fear of being labeled as kari, which hampers their mobility; who they meet, how they behave and when and to whom they talk to.

In Afghanistan the custom of Sawara allowed families to settle their feuds, based on murder or other conflicts, by giving away their women for conflict resolution to the other party. In pushto speaking culture of Afghanistan and Pakistan it is called sawara and in Farsi speaking cultures of Afghanistan it is called Baad.

The tradition of wata sata in Punjab and other areas of North India and Pakistan allows two families to give and receive a girl in marriage at the same time. So two brothers exchange their sisters for marriage. This in past was meant to reduce the burden of bride wealth or expenses of dowery. It was also considered a way of keeping control over the other family not to mistreat their daughter as the other family’s daughter was with them. But over the years it has become quite an abusive custom for both women and men.

In Afghanistan the same tradition is called Mukhi. It has exactly the same dynamics.

In most of the countries polygamy is a tradition that has made women suffer but in northern part of Nepal it is polyandry that becomes difficult to handle for women. This tradition gets a woman to marry three or four brothers together. This is done to keep the family together. It also keeps the property together for all the children. This situation is not comparable to polygamy as it is not a woman’s choice to pick out three or four different men but she is bound to marry all the brothers. This tradition at one point was also there in the east Punjab. It has more repercussions for women than advantages. In many cases the woman is beaten up by more than one husband. There are jalousies and complains that she favours one over the other.

In most of the South Asian countries the stigma on a divorced woman is strong. In the urban areas customs have changed but in rural areas it is not easy for a divorced woman to be remarried. This is common tradition in India, Bangladesh, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. In Pakistan and North India a divorcee woman is excluded from different folk rituals that are practiced with the bride and the groom; Putting hina on their hand, putting oil in their hair, giving sweets to the married couple etc. is all forbidden for these women to avoid any bad omen on the newly married couple. However, in the traditional culture of Maldives and parts of Bhutan being a divorcee is not seen as a problem at all.

Similarly, when a woman’s husband dies in Punjab she is forced to break all her bangles. Thereafter, she is not allowed to put on makeup and is pressured to stay in very simple clothes throughout her life. In India also, in rural areas, a window woman is not allowed to dress up at any time after she becomes a widow. Remarriage is also an uncommon phenomenon. In Afghanistan she is not supposed to move out of the house and is expected to stay out of the public gaze. In Nepal she is never allowed to wear red or bright colours through out her life and is supposed to wear white all the time. She is not allowed to leave the house for one year. That particular restriction applys to men in a similar situation also but their deviance is more easily accepted than women’s. Widows are not allowed to take part in puja, festivals or any family gathering like a wedding or other celebrations.

Puberty for women in many cultures is an embarrassment and not a celebration. In Nepal in some rural areas, when a young women has her first period she is sent into seclusion for 12 days. She cannot see the daylight or any man. She is not allowed to eat with her family or touch other’s food. Judho is the term used. Porasoreko (far to move ) implys, she should move far away from food. She cannot be a part of the puja or any festival. After 12 days she is brought out and all the things she had touched get washed. This is also called gufa rukhni. At times if the family is busy and do not want to wait for the first period of the young girl, they go ahead and do the seclusion for 12 days as a ritual and when it really happens they do not think they have to do it as they had already fulfilled the obligation. Thereafter every time she has her period she goes into seclusion for 4 days.

Similarly in other cultures of the SAARC region there is some stigma attached to women because of their periods. Just to clarify the concept of purity and impurity is not about cleanliness and dirtiness but it has directly to do with the stigma attached to something. Women are considered impure in several circumstances only because their period is considered impure. They are not allowed to say prayers, fast, recite the holy text, go to the graves, etc. In many shrines in Pakistan and India there is a sign that prohibits women to go in the inner pulpit of the shrine, where the grave of the saint is.

When a woman delivers a baby she is kept indoors for 40 days. In Punjab it is called chila. A woman is considered impure in these days. In Nepal, in some rural areas, women are banished to the cow shed to spend her 40 days. A high number of infant mortality results because of this practice.

In conclusion we see that folklore and traditional customs in the past and the present do give an important role to women as repositories of tradition. However upon analysis we find out that folkloric traditions do have a more positive affect on woman’s lives and can also have restrictive and damaging effect on them. With time the role of woman has changed. The urban and metropolitan areas have broken the traditions in many ways and have created new ones. Many break the tradition and continuously suffer from the social pressure and stigma. All this points out to the fact that folklore is not written in stone.

Folklore is what people collectively develop for themselves and like any aspect of a culture, this also changes with time and with the changing needs of people.

Our politics, technology and issues of urban life have all entered the folk poetry and folk songs. Our folklore is bound to be changed with time. So why not analyze it and just like any other change we leave out or discourage the traditions that sanction murders and put down certain groups in the society and encourage those that promote ethnical and gender harmony. We as people are legitimate users and makers of the folklore. An impression that folklore is a sacred cow and should not be touched but only be documented, studied and revived as is does not help women. On the other hand having a vision of folklore which is romanticized versions of old days when people use to sit under the tree while animals grazed and someone played the flute is not very helpful.

The folklore of any country or region has to be pruned and transformed by its people. It has to be done with full ownership and a commitment for our fellow beings to enjoy the basic human rights and dignity. I will end with a small example, in United states children had been playing and singing this poem for decades.

Ini mini mina mo

catch a niger by its toe,

if he screams let him

go ini mini mina mo

Niger you know is a derogatory word for a black person. For years it was sung by children but when the awareness of what it actually implies became vivid it was quietly changed to catch a tiger by its toe. So the current generation of children do not even know that there was the word niger in there poem.

Grooming and cleaning out of the folklore is the collective responsibility of the society and we should not shy away from it. It is time that we do take out sanctioning murder of women from our customs and stop using a woman’s name as a swearword in our folklore. We have ample folkloric customs, poetry, songs and rituals that encourage harmony, equality and dignity for all. We should happily revive those and be proud of it.